Regenerative Medicine to the Rescue

New cell therapies offer healing and hope where other approaches can’t reach.

COVER STORY

By John Soeder

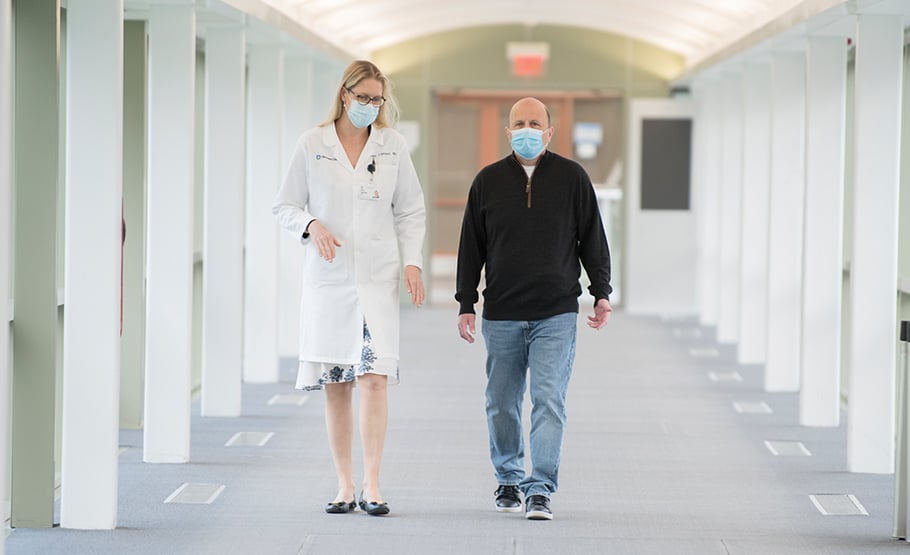

"The healing that we’re seeing is remarkable,” says Dr. Amy Lightner, a colorectal surgeon and researcher who leads the new Center for Regenerative Medicine and Surgery in Cleveland Clinic’s Digestive Disease & Surgery Institute. | Photo: Yu Kwan Lee

If you want to start to wrap your head around the concept of regenerative medicine, look no farther than the nearest mirror.

When you get there, study your face. Done? Excellent. OK, now stop reading, let a few weeks go by and then have another gander at that mug of yours.

Go ahead — we’ll wait.

[a few weeks later]

Hello again! Did you notice much of a difference when you went back to the mirror? Probably not. Here’s the fascinating part, though: You’re the proud owner of a new face.

Sure, it looks familiar. But the cells that you previously saw on the surface of your visage are history. They’ve been replaced by fresh cells that got their start deep within your epidermis. They grew and divided and gradually made their way along a river of cells to the outermost layer of skin, where old cells that have died are continually sloughed off to make way for new cells.

It’s true: Our bodies know a thing or two about regeneration. And we’re learning more all the time, thanks to regenerative medicine. This burgeoning interdisciplinary field seeks to restore healthy form and function by repairing, replacing or rejuvenating cells, tissues or organs that are depleted, damaged or diseased.

“Regenerative medicine is really a catchphrase for a lot of different types of therapies,” says Timothy Chan, MD, PhD, Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Immunotherapy and Precision Immuno-Oncology.

Broadly speaking, this isn’t an entirely new concept. Skin grafts, which originated in India some 3,000 years ago, could be considered a form of regenerative medicine. What is new is the ever-expanding menu of cell therapies that fall under the same umbrella.

“When we talk about regenerative medicine today, a lot of what we’re talking about is cell therapy,” says Dr. Chan, who also leads (with Stan Gerson, MD) the National Center for Regenerative Medicine, a Cleveland-based consortium whose founding partners include Cleveland Clinic, Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals.

“Regenerative approaches are very important when you have to generate critical cells,” Dr. Chan says. “A lot of areas of investigation utilize stem cells, and it rolls into utilizing engineered T cells and other types of cells to elicit a fix for a disease.”

It could be cancer. Or multiple sclerosis. Or inflammatory bowel disease. With those diseases and others, regenerative medicine is bringing the promise of healing to more and more patients. Read on to meet three of them.

For Kevin Kelley — seen here with his wife, Karen, on the Lake Erie shore — beating lymphoma involved two types of regenerative medicine: a bone marrow transplant and CAR-T cell therapy. | Photo: Stephen Travarca

For Kevin Kelley, the bad news came out of nowhere. “I woke up one morning,” he recalls, “and it felt like somebody had stuffed half a banana under the left side of my jaw.” The IT data security analyst from the Cleveland suburb of Rocky River, Ohio, considered himself to be in good health, aside from the hypertension that ran in his family and a recent pulmonary embolism that was successfully treated. A competitive swimmer, he swam a couple of miles almost every day, either in Lake Erie or in a pool.

A biopsy of Kelley’s swollen gland revealed an aggressive form of non-Hodgkins lymphoma, a malignant cancer that originates in the lymphatic system, a network of vessels, tissues and organs that helps remove toxins and waste from our bodies.

To fight the disease, Kelley and his oncologist, Brian Hill, MD, PhD, of Cleveland Clinic, turned to regenerative medicine — not once, but twice. “His case is compelling because it highlights where regenerative medicine has been and where regenerative medicine is heading,” says Dr. Hill, Director of the Lymphoid Malignancies Program in Taussig Cancer Institute.

Kelley received a bone marrow transplant and CAR-T cell therapy. Bone marrow transplants, which have been used for decades, transfer healthy blood-forming cells into a person with blood cancer. CAR-T cell therapy, which the Food and Drug Administration initially approved in 2017, modifies a patient’s own immune cells to kill cancer cells.

First, though, Kelley underwent six cycles of chemotherapy. Through it all, he continued to swim as often as he could. His care team even timed the treatments so he and his new bride, Karen, could enjoy a Grand Cayman honeymoon.

Unfortunately, a few months later, a biopsy showed that Kelley wasn’t cancer-free. The next step was a bone marrow transplant, immediately preceded by more chemotherapy. “Very high doses of chemotherapy are delivered with the intention of eliminating the lymphoma,” Dr. Hill says. “In the process, though, the patient’s bone marrow is eradicated, too. So you have to collect their bone marrow ahead of time and then give it back to them after the chemotherapy.”

In Kelley’s case, the transplant was autologous, meaning he was his own donor. (Allogeneic transplants entail a matched donor.) During the transplant, more than 100 million hematopoietic stem cells were delivered directly into his bloodstream through a special type of IV. For good measure, a chaplain blessed the cells beforehand, at Kelley’s request. “I figured every little bit helps,” he says.

Like salmon swimming upstream to spawn, the cells knew where to go and what to do when they got there, regenerating healthy marrow in the bones.

For Kelley, the road to recovery included a three-week stay in the hospital. After another month of rest at home, he began swimming again, slowly but surely regaining strength. He was declared in remission, although the respite was short-lived. Less than a year after the bone marrow transplant, a scan showed new activity. A lymph node biopsy confirmed it: The lymphoma was back.

Kelley didn’t hesitate when Dr. Hill recommended a new line of attack: CAR-T cell therapy. To get the ball rolling, T cells — which are white blood cells — were collected from Kelley through a procedure called leukapheresis. The T cells were then shipped off to a lab, where they were genetically altered. New chimeric antigen receptors (CAR for short) on the surface of the T cells would allow them to carry out a seek-and-destroy mission against cancer cells. In the meantime, Kelley had another course of chemotherapy. When the manufactured CAR-T cells were ready, hundreds of millions of them were infused into his bloodstream. After a week in the hospital, he was back home and on the mend.

“With CAR-T cell therapy, instead of just hammering away at the cancer cells with traditional chemotherapy drugs that poison the cells, the idea is to invoke the power of the body’s own immune response to attack the cancer,” Dr. Hill says.

By way of an explanation, Kelley offers an analogy that any fan of old-school video games will appreciate: “Suddenly, your body is playing Pac-Man. Once those manufactured T cells are put in you, they’re on the hunt. When they find a cancer cell, they destroy it. They’re just gobbling it up.”

CAR-T cell therapy isn’t without side effects, which can include flu-like symptoms as well as neurologic events that can result in confusion. Nonetheless, this particular form of regenerative medicine shows great promise. “I’m very optimistic for the future of this treatment approach,” Dr. Hill says.

As for Kelley, he’s back in remission. He plans to swim in a couple of upcoming 8-mile, open-water races: one in the Florida Keys and one around Mackinac Island in Michigan. The latter will be a fundraiser for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

“I feel great,” Kelley says. “Now it’s time to go have some fun.”

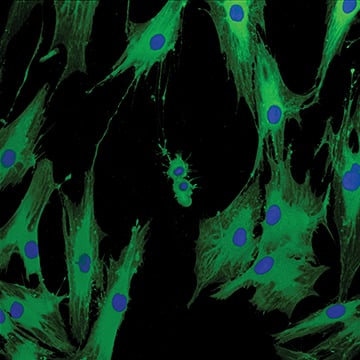

Photo: Lerner Research Institute Imaging Core

Stem Education

In this story, you’ll read a lot about stem cells. What exactly are these little wonders? Stem cells are self-replicating. They’re undifferentiated, meaning they don’t have specialized features. And they can divide and develop into other types of cells to form various tissues.

Stem cells themselves come in many different varieties. The bodies of fully grown adults abound with adult stem cells, capable of developing into a limited range of other cell types.

Two examples of adult stem cells that play prominent roles in regenerative medicine are hematopoietic stem cells and mesenchymal stem cells. Hematopoietic stem cells, most commonly found in bone marrow, can differentiate into the building blocks of blood, including red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets. Mesenchymal stem cells — also right at home in bone marrow, as well as in umbilical cord blood and in fat tissue, among other places — can give rise to bone, cartilage, muscle and connective tissue.

“I’m hopeful because I think we’re on the right path,” says Cindy Kopitke, right. She saw favorable results after Dr. Jeffrey Cohen, left, invited her to participate in a clinical trial using mesenchymal stem cells for patients with progressive multiple sclerosis. | Photo: Stephen Travarca

Cindy Koptike wanted to make a positive difference. Not just for herself, but for others who, like her, are battling progressive multiple sclerosis. When neurologist Jeffrey Cohen, MD, of Cleveland Clinic told her about a Phase 2 clinic trial to treat the neurodegenerative disease with regenerative medicine, Kopitke was eager to participate.

“I’m willing to do whatever it takes,” she says. “I need to have a purpose in life. If I could do something that might help other people with the same diagnosis as I have, I was ready.”

Kopitke, who lives near Toledo, Ohio, is no stranger to helping people. A retired certified orthotist, she used to make custom orthotic braces.

After experiencing double vision and balance issues, she was diagnosed with MS a decade ago. “I went downhill quickly to the point where I couldn’t work anymore,” she says.

In patients with MS, the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy cells in the myelin, a protective sheath surrounding nerves in the brain and spinal cord. Some patients develop a progressive form of the disease, which may result in increasing levels of visual, motor and cognitive impairment and further disability.

“The medicines that we use to treat relapsing MS are not very effective for more severe progressive MS,” says Dr. Cohen, Director of the Experimental Therapeutics Program at Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis Treatment and Research. “The disease produces damage in the nervous system, and this damage itself not only impairs function, but sets up a situation where preexisting damage leads to further damage. The body, including the brain, repairs itself naturally. But if we can’t get the MS under control, the repair never catches up. None of our currently available medicines can restore damage that has already occurred. So a big priority is developing approaches for repairing this damage.”

Kopitke was part of an industry-sponsored trial at Cleveland Clinic and other sites that used mesenchymal stem cells to treat progressive MS. It refined techniques from other studies, including a previous trial by Dr. Cohen that was funded with grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Defense.

Like many patients, Kopitke has been able to manage the inflammatory component of MS with medication. But damage caused by the disease had left her with residual neurologic disability, including weakness and difficulty with gait.

Kopitke’s mesenchymal stem cells were obtained via a bone marrow aspiration. In a lab, the cells were grown in culture and treated to increase their production of so-called trophic factors, which are molecules that support cell function and promote repair. Kopitke then received the manipulated cells through a spinal tap, at which point they got busy.

“One of the reasons why mesenchymal stem cells are of great interest is because they seem to have the ability to seek out areas of abnormal inflammation or areas of damage in the body,” Dr. Cohen says. “We suspect their natural job is to promote repair when and where it’s needed.”

All told, Kopitke received three treatments, two months apart. A few days after the first treatment, she attended a picnic at her brother’s home. She noticed a difference — and so did her family. “Before, I would’ve wanted to go home early because I knew I was going to fall asleep,” she says. “After I got the stem cells, I stayed awake the whole time, and I could walk down the back stairs and hang out with everyone in the backyard.”

Overall, patients in the trial showed improvement on a variety of neurologic tests. They also had decreases in biomarkers associated with damaging inflammation and increases in beneficial neuroprotective molecules.

“The findings are encouraging,” Dr. Cohen says. “But there are still a lot of unanswered questions. What’s the best way to grow the cells? How many do you need to inject? How often do you need to inject them? What’s the best way to administer them?” We’re still learning about the practical aspects. But once you have some preliminary success — an indication that you’re on the right track — the momentum builds very quickly.”

For patients with progressive MS, regenerative medicine using mesenchymal stem cells might someday offer even more hope where other medical approaches cannot.

“We have more than 20 medications to prevent relapses in MS, but we have only two medications that are approved for progressive MS — and they don’t work very well,” Dr. Cohen says. “Anything that could promote repair and restore function would be, in fact, game-changing.”

Kopitke, for one, believes there is good reason to be optimistic. “I’m doing so much better,” she says. “I can walk straighter. I can walk faster. I’m starting to build muscle. And I have more energy, too. I’m hopeful because I think we’re on the right path.”

“Mesenchymal stem cells…seem to have the ability to seek out areas of abnormal inflammation or areas of damage in the body,” says Dr. Jeffrey Cohen. “We suspect their natural job is to promote repair when and where it’s needed.”

“My mindset is: I’m cured,” says Gary Jacobson, right. He turned to Dr. Amy Lightner, left, for cell therapy to treat painful complications of Crohn’s disease. | Photo: Stephen Travarca

Gary Jacobson can sum up the benefits of regenerative medicine in eight words: “I get to have a normal life again.” This self-described “part-time hedge fund manager and part-time stay-at-home father of three” was an overworked Wall Street analyst in the 1990s when he ended up in a New York City hospital, doubled over in pain. After a battery of tests, it was determined that he had Crohn’s disease, a chronic inflammatory bowel disease whose symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, rectal bleeding and weight loss.

Ten years ago, the situation went from bad to worse when Jacobson developed perianal fistulas. Think of them as miniature canals of misery, funneling drainage from the rectum to the skin around the anus, which makes it necessary for people with fistulas to wear pads under their clothes at all times.

“I lived painfully with the complications,” Jacobson says. “The drainage was constant. It hurt to sit down. It felt like I was sitting on needles. And I spent years on antibiotics because the area was very prone to infection.”

He was desperate for relief. “I tried everything,” he says. “I was treated in Spain. I went through a phase where I tried Eastern medicine. I tried every drug that doctors wanted me to try. I tried setons, which are thin cords that drain the fistulas to prevent infection.”

He also had an ostomy, although he drew the line at having his rectum and anus permanently removed and passing waste into a pouch for the rest of his life. “That, to me, wasn’t a solution,” he says.

Enter Amy Lightner, MD, FACS, a colorectal surgeon and researcher at Cleveland Clinic who treats inflammatory bowel disease with regenerative medicine. Jacobson had become aware of her work through the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation, where he served as a Chapter President. At the height of the pandemic in 2020, he drove eight hours from his home in Chappaqua, New York, to meet Dr. Lightner at Cleveland Clinic’s main campus “She examined me for 10 minutes and told me, ‘You’re a perfect candidate for my trial,’” Jacobson recalls.

Once again, we’re talking about mesenchymal stem cells to the rescue.

A patient with Crohn’s disease, for example, has low levels of T regulatory cells (which modulate the immune system) and low levels of M2 macrophages (which reduce inflammation and heal tissue), according to Dr. Lightner, Director of the new Center for Regenerative Medicine and Surgery in Cleveland Clinic’s Digestive Disease & Surgery Institute.

“Mesenchymal stem cells are immunomodulatory, increasing levels of these cells in the local environment,” Dr. Lightner says. “They’re also restorative. They repair tissue.”

Jacobson underwent a couple of preliminary surgeries to clean up his bowels. “My rectum basically could be described as Swiss cheese,” he says. Then, on New Year’s Eve, he got the call: The mesenchymal stem cells (derived from the bone marrow of a healthy donor) were ready — how soon could he return to Cleveland Clinic?

Several days later, he was under sedation for a minimally invasive procedure. Dr. Lightner used a syringe to inject 75 million mesenchymal stem cells directly into Jacobson’s rectal wall and along the fistulas. In addition to boosting desired immune cells in those areas, the stem cells reduced inflammation and allowed the growth of new, healthy tissue.

After one night in the hospital for observation, Jacobson was good to go. Within a week, his symptoms showed signs of improvement. Today, with his Crohn’s disease in check with medication and the fistulas completely healed, he feels like a new person.

“No more pain, no more pads, no more fear of embarrassment,” Jacobson says. “My mindset is: I’m cured.”

Regenerative medicine isn't just generating cells, tissues and organs.

It’s generating excitement. “The healing that we’re seeing is remarkable,” Dr. Lightner says. “It’s very promising, especially for patients who have no other options.”

With the Center for Regenerative Medicine and Surgery, she hopes to bring the benefits of cellular therapeutics to even more people. Dr. Lightner is currently conducting multiple Phase 1 and Phase 2 trials of stem cell therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

She also is collaborating with other caregivers across Cleveland Clinic. “The idea is for the center to work across institutes,” Dr. Lightner says.

She recently treated a patient in the Dermatology & Plastic Surgery Institute who experienced a face transplant rejection. “In the transplant patient population, the Achilles’ heel for any transplantation is rejection,” Dr. Lightner says. “With rejection, there are areas of unmet need involving inflammatory or immune components that we can address with cell therapy.”

Regenerative medicine lends itself to the “team of teams” approach that has always been central to the identity of Cleveland Clinic. Its Blood and Marrow Transplant Program includes a new Cellular Therapy Assist Team of physicians, nurses, researchers and others who are sharing their expertise to facilitate clinical trials of cellular therapeutics for various cancers, neurological diseases and rheumatic diseases.

“With cellular therapy, we see a vast amount of overlap,” says hematologist and oncologist Betty Hamilton, MD, Associate Director of the Blood and Marrow Transplant Program. “In our program, we’re well-versed in taking stem cells and then putting them back in a patient. As cellular therapies expand, we’re working closely with colleagues who specialize in different diseases. Ultimately, these new therapies will help us cure more patients or improve their outcomes.”

In the meantime, the buzz about regenerative medicine continues to build.

“Cell therapy is still in its infancy,” Dr. Lightner says. “As we learn more, we’ll end up engineering cells that are targeted for a specific patient with a specific disease. With regenerative medicine, we’re entering a new era where we’re using these cellular therapeutics to change the way we think about disease and the way we treat disease. This is the future of medicine.”

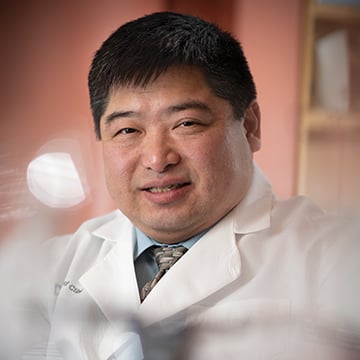

Photo: Stephen Travarca

The Need Is Now

In a field evolving as rapidly as regenerative medicine, philanthropy accelerates breakthroughs that change lives and save lives.

“The current generation of cell therapies was created through a process of discovery fueled by philanthropic gifts,” says Dr. Timothy Chan, pictured, of Cleveland Clinic.

New cell therapies and other forms of regenerative medicine will require additional support.

“Developing these approaches to deliver world-class cell therapy at Cleveland Clinic is a critical part of our vision for caring for patients with cancer and many other diseases,” Dr. Chan says. “Before a great idea can go on to become a standard of care, the early development almost always happens internally — and it doesn’t happen without philanthropy.”