THEN NOW NEXT

Atrial Fibrillation

By Jill Stefancin

Electrocardiogram machine at Cleveland Clinic in 1921. | Photos: Cleveland Clinic Archives (EKG Machine); Marty Carrick (Ablation); Don Gerda (Dr. Chung)

Electrocardiogram machine at Cleveland Clinic in 1921

THEN

Ever since physicians began taking the pulse as a barometer of health, they’ve noticed rhythm irregularities, using terms like “ataxia of the pulse,” “delirium cordis” and “pulsus irregularis perpetuus” to describe them. Early treatments focused on slowing the heart rate with medications such as digitalis and quinine. By the early 1900s, the electrocardiogram was invented, and a connection was made between the irregularity of the pulse and atrial fibrillation (AFib), an irregular rhythm in the heart’s upper chambers. In 1970, the Framingham Heart Study published an alarming statistic that showed that people with AFib were five times more likely to have a stroke.

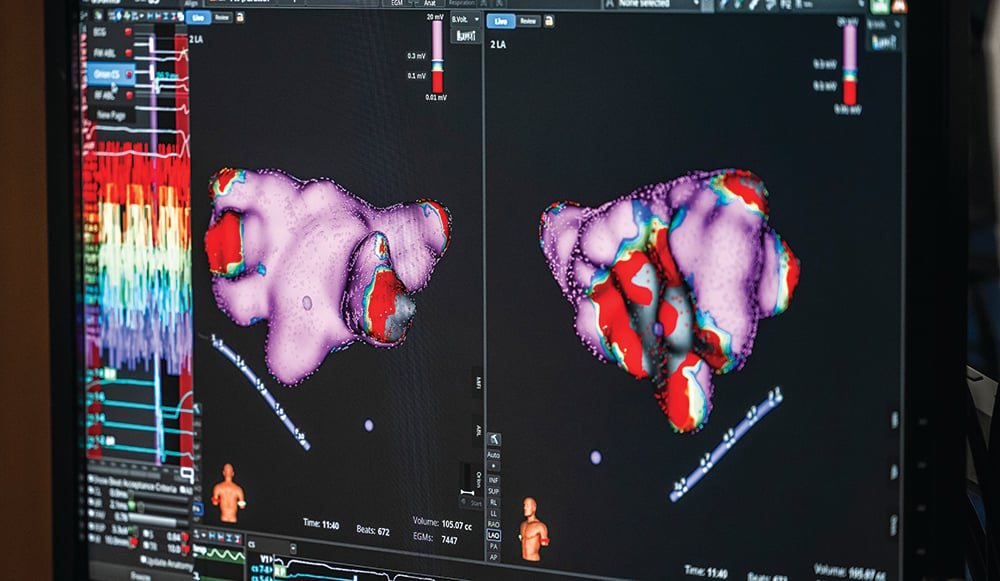

A pulsed-field ablation treatment for AFib

NOW

Treatments focus on preventing the arrhythmia with lifestyle changes, using drugs targeting the electrical system or catheter ablation to isolate the pulmonary veins where initiating beats of AFib occur. In 2020, a Cleveland Clinic-led study found that earlier intervention with catheter ablation may keep patients free from AFib longer and prevent the disease from progressing into more persistent atrial fibrillation. However, it has been over a decade since a new drug was approved to treat AFib.

Dr. Mina Chung

NEXT

Supported by grants from the American Heart Association and the National Institutes of Health, the TRIM-AFib (Targeting Risk Interventions and Metformin for Atrial Fibrillation) clinical trial launched in 2018 to see if a diabetes drug, metformin, along with lifestyle and risk factor modification, could target AFib’s underlying factors by improving heart muscle metabolism.

In late 2024, the initial results of the study after one year of follow-up showed that metformin did not significantly lessen the burden of AFib. Unexpectedly, the standard-of-care study group, where subjects received written information about lifestyle changes and risk factor management, was most effective.

Researchers noted that all the study groups lost weight, decreasing the AFib burden and suggesting that novel therapeutics for weight loss/diabetes may provide benefit in the prevention and treatment of AFib.

Cleveland Clinic cardiologist and researcher Mina Chung, MD, who led the study, notes that TRIM-AFib is a two-year trial and that the interventions, including metformin, may perform better over time.

Undaunted, the researchers are continuing their work, including microbiome studies and analysis of biomarkers from blood samples. The data promises interesting insights into daily AFib burden, long-term longitudinal changes and what happens after interventions like cardioversion and ablation.