THEN NOW NEXT

Brain Aneurysm

By Jill Stefancin

Photo: Cleveland Clinic Archives

Then

A brain aneurysm happens when a bulge forms in a weakened area in a blood vessel in the brain and fills with blood. If the aneurysm ruptures, surgery is necessary. Since the late 1930s, traditional surgical treatment involved shaving a patient’s head, removing a piece of the skull to see the aneurysm and placing a clip across it, pinching it off from circulation and preventing it from rupturing. While effective, it’s risky and has a lengthy recovery time. W. James Gardner, MD, Cleveland Clinic’s Chief of Neurosurgery from 1929 to 1962, was a pioneer in the field. He developed the Gardner Neurosurgical Chair, which allowed neurosurgeons to operate on parts of the brain that were difficult to reach when a patient was lying down.

Now

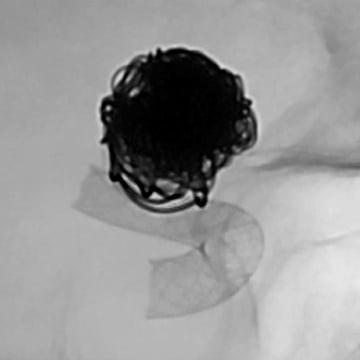

Thanks to MRIs and CT scans, many aneurysms are discovered before they rupture. If surgery is needed, a flexible catheter is inserted in a blood vessel, usually in the groin or wrist, and threaded to the brain, where the surgeon places a tiny ball of wires or a mesh ball in the aneurysm. This blocks the flow of blood into the aneurysm, eliminating the risk of rupture. A new variation is the "flow diversion" technique, in which a mesh tube (the curved gray item in this photo) is placed in the artery to divert blood flow from the aneurysm (seen here as a dark mass), which eventually clots and dissolves.

Among the first physicians in the U.S. to use this technique was Mark Bain, MD, Head of Cerebrovascular and Endovascular Neurosurgery in Cleveland Clinic’s Neurological Institute.

Next

3D-printed anatomic models currently help guide complex surgeries ranging from liver transplants to congenital heart defect repairs. Next up? Aneurysms. 3D printing creates a true-to-size model of the aneurysm such as the one pictured above, which includes a small metal clip used to stop blood flow. The model allows doctors to visualize the surgical approach before a single incision is made, according to Dr. Bain. In addition, the model provides better patient education and better equipment selection for procedures. Using 3D models for brain surgeries also presents the potential for reduced operating time, fewer complications and enhanced patient outcomes. As 3D printing revolutionizes medicine, philanthropic funding is helping to advance its use in surgeries, research and medical education.