THE 1940s

Anchors Aweigh

Cleveland Clinic physicians established Mobile Hospital No. 4 in the South Pacific.

Cleveland Clinic’s Naval Reserve Unit and other officers pose for a group photo in New Zealand. |Photo: Cleveland Clinic Archives | Colorized by Sanna Dullaway

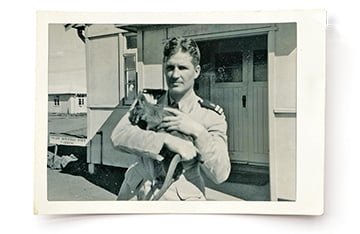

During his tour of duty in the South Pacific, Dr. George “Barney” Crile Jr. befriended a wallaby named Franklin Roosevelt in honor of the U.S. Commander in Chief. | Photo: Cleveland Clinic Archives

During World War II, on battlefields and bases throughout Europe and the Pacific, Cleveland Clinic caregivers proudly answered the call of duty. Among them were the members of Cleveland Clinic’s Naval Reserve Unit. Their ranks included physicians George “Barney” Crile Jr., MD; William Engel, MD; A. Carlton Ernstene, MD; W. James Gardner, MD; Roscoe Kennedy, MD; William Nosik, MD; Joseph Root, MD; and Edward Ryan, MD.

Led by Lt. Cmdr. Gardner, the unit was called to active duty in 1942. Starting in March, they spent two months in training at the Brooklyn Naval Yard in New York City. At that point, boredom was the enemy — Dr. Crile said there was little to do but read the newspaper.

In May, they finally set sail for New Zealand. Once there, they established Mobile Hospital No. 4, the first of its kind in the South Pacific. The goal was for the facility to be ready for the Guadalcanal campaign, which would take a heavy toll on Allied forces. Between August 1942 and February 1943, the first major offensive in the Pacific theater saw more than 7,000 killed and more than 7,000 wounded.

Cleveland Clinic physicians helped corpsmen construct the portable hospital, shipped piece by piece from the United States, on a muddy cricket field on the outskirts of Auckland. Within three weeks, Mobile Hospital No. 4 was up and running — and just in time. The hospital ship Solace arrived mid-August with the first patients.

Over the next 18 months, Cleveland Clinic’s Naval Reserve Unit found itself dealing more with tropical diseases, including malaria, than with battle wounds. Eventually, some of the officers were assigned to other stations. In his journal, Dr. Kennedy wrote: “What Sherman said about war [‘War is hell’] still holds.”

When the physicians returned home after the war, Cleveland Clinic paid their full salaries, minus their naval pay.

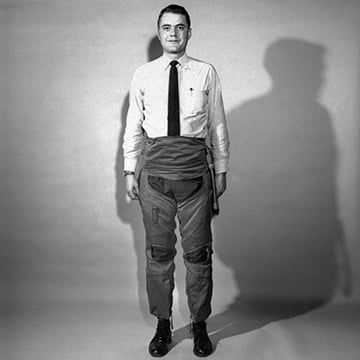

Photo: Cleveland Clinic Archives

Pneumatic Chic

Little did Dr. George Crile Sr. know when

he developed a pneumatic rubber suit in the early 1900s that it would someday prove useful in America’s war efforts. Inflated with a bicycle pump, the suit originally was designed to regulate blood

pressure during surgery. Dr. Crile ultimately deemed his invention “cumbersome and uncomfortable” and set it aside. Decades later, in the 1940s, he realized that the technology could be adapted to prevent fighter pilots from blacking out when subjected to high G-forces. This led him to collaborate with the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company on a G-suit (right) for military use.