THE 1930s

Best. Job. Interview. Ever.

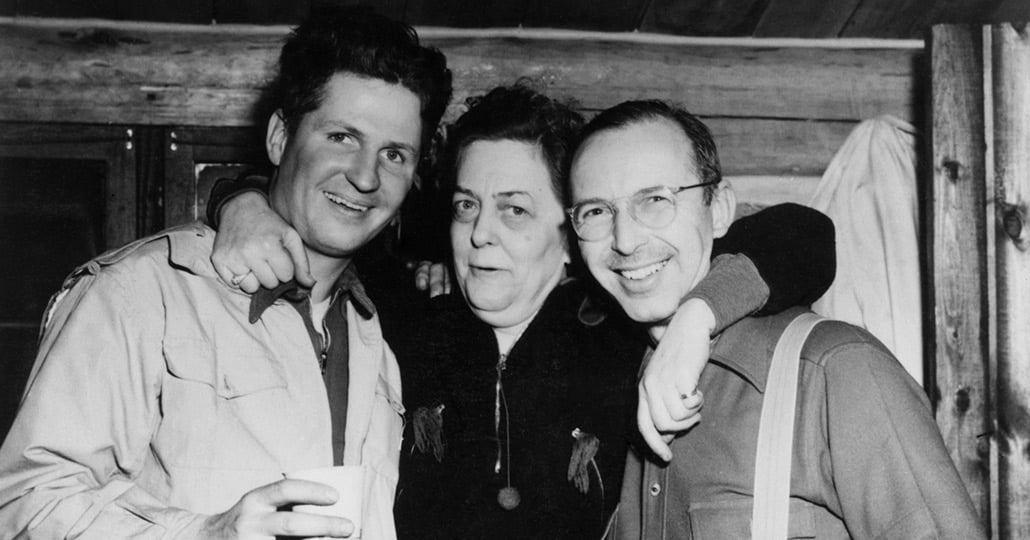

Dr. W. James Gardner (right) and Dr. George “Barney” Crile Jr. (left) flank Lou Adams, the head of Anesthesia Services at Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Gardner and Dr. Crile served together in Cleveland Clinic’s Naval Reserve Unit during World War II. This photo was taken at a send-off party before they reported for active duty. | Photo: Cleveland Clinic Archives

After Charles Locke, MD, Cleveland Clinic’s first neurosurgeon, died in the 1929 Cleveland Clinic disaster, George Crile Sr., MD, and William Lower, MD, found themselves with a key position to fill. W. James Gardner, MD, came highly recommended from the University of Pennsylvania.

At a conference in Erie, Pennsylvania, Dr. Lower talked Dr. Gardner into driving back to Cleveland with him. The following morning, Dr. Lower brought the job candidate to Cleveland Clinic and led him straight into the room of a patient who couldn’t speak.

“What do you think of this lady?” Dr. Lower asked.

“She has an unlocalized brain tumor,” Dr. Gardner replied.

“Yes, but where is it?”

“Well, since she can’t talk, it’s in Broca’s area.”

“Broca’s area? Where’s that?”

“Right here.” Dr. Gardner pointed to his left temple.

That was all Dr. Lower needed to hear. He popped the big question: “Would you like to operate on her?”

Dr. Gardner mentioned something about having to catch the afternoon train back to Philadelphia. His excuse fell on deaf ears.

“Come with me,” Dr. Lower said. He took Dr. Gardner to an operating room. Sterilized surgical instruments were laid out, and an anesthetist and a nurse were at the ready. All the scene needed was a skilled neurosurgeon.

Dr. Gardner agreed to give it a go. “Billy Lower wasn’t one to buy a pig in a poke — he wanted to see action!” he later recalled. “Luck was with me. I turned down the left frontal flap, opened the door, and a globular meningioma [a tumor in the membranes surrounding the brain] almost rolled out to the floor. I finished the operation in 2 hours and 20 minutes — and the job was mine.”

Over the course of a career that spanned more than four decades at Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Gardner was a pioneering neurosurgeon who trained many others in the field. He also had a hand in numerous innovations. Among them were “the Gardner chair,” which kept patients safely in a seated position during cranial surgery, and Gardner-Wells cervical tongs, still used today for spinal traction.