THE 1920s

Grief Would Be Defeat

One of the deadliest hospital disasters in U.S. history took 123 lives.

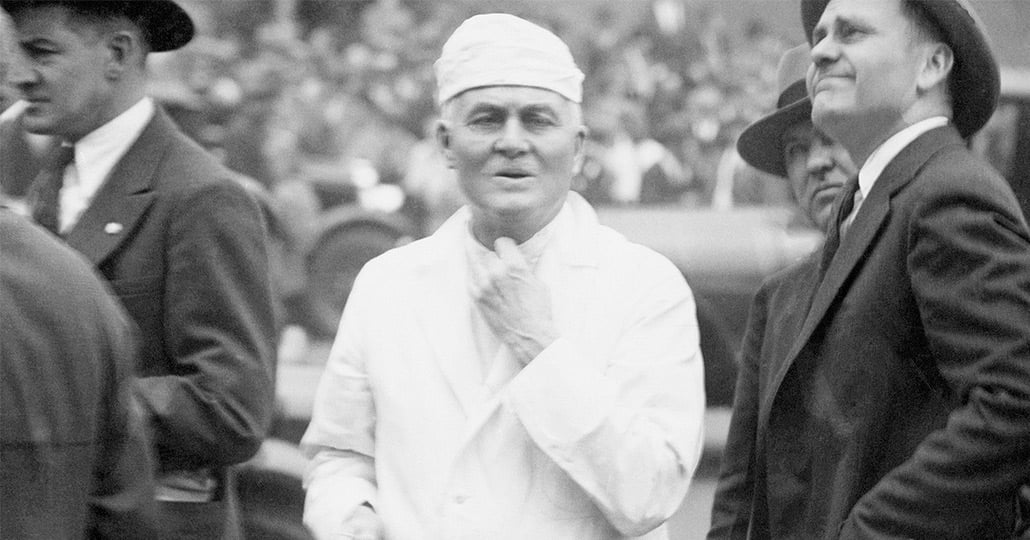

Dr. George Crile Sr., who had been performing surgery in a different building, arrives at the scene of the disaster. “I saw nothing in France so terrible,” he later wrote. “It was a crucible.” | Photo: Cleveland Clinic Archives

Hundreds of volunteers aided police officers, firefighters and caregivers in the all-out rescue effort. | Photo: Cleveland Clinic Archives

Shortly after 9 a.m. on Wednesday, May 15, 1929, a leak was found in a high-pressure steam line in the basement of the Clinic Building, in a dark and poorly ventilated storage room estimated to contain more than 4,000 envelopes of X-ray film. In the early 1900s, X-rays were made on plates of nitrocellulose, an extremely volatile substance. When nitrocellulose is heated, it produces high concentrations of toxic chemicals.

Steamfitter Buffery Boggs encountered clouds of thick smoke pouring from the area around the exposed pipe. After he tried in vain to put out the fire, Boggs and an assistant custodian attempted to escape. The first of several explosions knocked both men through a basement window, miraculously allowing them to scramble to safety.

A nearby fire company was the first to respond. When they arrived, most of the building was obscured by a dense, yellow-brown cloud. More alarms brought more firefighting equipment and rescue squads. Ladders were raised to evacuate people who appeared at the windows. Another explosion blew out the skylight and parts of the ceiling of the fourth story, liberating an immense cloud of deadly vapor.

It was not a raging fire that caused so much loss of life, but rather the release of poisonous gas, which spread quickly through ducts servicing every room in the building. A report issued by the National Fire Protection Association in the wake of the disaster stated, “The most diabolical cunning could scarcely have devised an arrangement more surely calculated to spread death throughout the building.”

The heroism of caregivers, firefighters, police officers and many volunteers saved dozens of lives. An impromptu triage was carried out on the grass in front of the building. Many of the physicians on the scene, including George Crile Sr., MD, recognized the injuries as similar to those they witnessed in World War I, in which poison gas caused a highly fatal “lung edema.”

This excerpt is adapted from To Act as a Unit, the official history of Cleveland Clinic. The updated and expanded Centennial Edition, by Executive Editor John Clough, MD, and Editors John Mangels and Steve Szilagyi, will be published soon.

Visit clevelandclinic.org/CentennialBrandStore

to purchase your copy.

Edith Morgan, who had served as a nurse in the Lakeside Unit, was working as a receptionist in the main waiting room. She tried to calm hysterical patients and help them get out. She later reported to the hospital building, where she continued to help care for victims until she collapsed.

William Brownlow, head of the Art and Photography Department, had taken the day off but returned to Cleveland Clinic to retrieve a forgotten item. While he was there, the main explosion occurred. He stayed to help, smashing a window on the third floor to get people out to a ladder. During these rescue efforts, he breathed the fumes and died.

Telephone operator Gladys Gibson died at her desk, with the cords on her switchboard plugged into lines throughout the building. She had remained at her post to alert others to the emergency, when she could have easily escaped through a window only a few feet away.

After the disaster, community leaders quickly came to the aid of Cleveland Clinic, which took up temporary quarters in a former dormitory across the street. Gifts totaling more than $30,000 (the equivalent of nearly half a million dollars today) poured in to help rebuild, but Cleveland Clinic opted to return the money — with interest — and finance its own recovery.

The challenges for the surviving founders were immense. They were now responsible for the human and financial losses; the challenges of rebuilding; corresponding with the throngs of the sympathetic, the angry and the grieving; and dealing with the legal morass that followed, all while returning to work.

By Friday of the same week, Dr. Crile was back in the operating room, doing what he did best. “Grief would be defeat,” he told his wife, Grace. “This has come to us, and we must build something constructive out of it.”