Meet the Founders

Four distinguished physicians. Four distinct personalities. One common goal: Create a new medical institution where specialists could exceed the sum of their parts and come together to advance patient care, research and education.

ORIGINS

Cleveland Clinic was founded by Dr. Frank Bunts, Dr. George Crile Sr., Dr. John Phillips and Dr. William Lower. | Photos: Cleveland Clinic Archives | Colorized by Sanna Dullaway

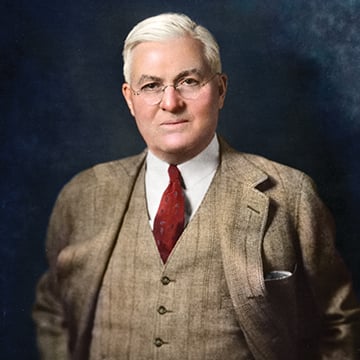

Frank Bunts, MD

1861-1928

Dr. Frank Bunts was the first of the founders to die, but his passion for training future physicians would live on in the Bunts Education Foundation at Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Bunts “was invaluable in our association,” Dr. George Crile Sr. said. “He was the one that gave it respectability.”

Dr. Bunts was born June 3, 1861, in Youngstown, Ohio. He attended the U.S. Naval Academy, then enrolled in medical school at Western Reserve University. After graduating as valedictorian in 1886, Dr. Bunts interned at St. Vincent Charity Hospital in Cleveland. In 1888, Dr. Bunts and Dr. Crile joined the practice of Frank Weed, MD, in Cleveland. Following Dr. Weed’s death in 1891, his assets were purchased by Dr. Bunts and Dr. Crile, who asked Dr. William Lower to join them.

Dr. Bunts served in the Ohio National Guard during the Spanish-American War. He later rejoined his partners in their Cleveland practice until they shipped out with the Lakeside Unit to Rouen, France, during World War I.

After co-founding Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Bunts — whose specialties were breast disease and cancer — also remained Chief of Staff at St. Vincent Charity Hospital. He trained residents there and at Cleveland Clinic and taught surgery at Western Reserve University. His sudden death from a heart attack on November 28, 1928, shocked his colleagues. The education foundation established at Cleveland Clinic in 1935 and named in his honor lives on today as the Education Institute.

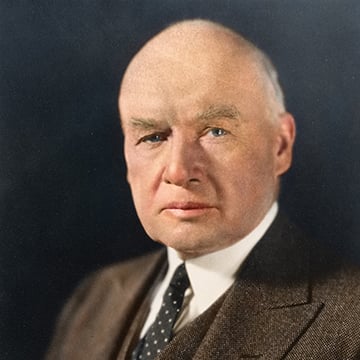

George Crile Sr., MD

1864-1943

The world was Dr. George Crile Sr.’s classroom. From the streets of Cleveland to the World War I hospitals of France, this country boy-turned renowned surgeon revealed a quenchless intellectual curiosity.

Dr. Crile was born November 11, 1864, and raised on a farm near Chili, Ohio. A door-to-door physician inspired him to attend Wooster University’s Medical Department, where Dr. Crile received his MD in 1887. After watching a friend whose legs were amputated die from shock, Dr. Crile had an epiphany. “I was … baffled over the inefficiency of treatment,” he said. He later pioneered “shockless surgery.”

By 1892, he was in practice in Cleveland with Dr. Frank Bunts and Dr. William Lower. In 1906, Dr. Crile performed the world’s first successful human-to-human blood transfusion. A founding member of the American College of Surgeons, he was a boundary-pusher who once caused an uproar by bringing a phonograph into an operating room.

Though Dr. Crile was 56 when Cleveland Clinic opened, the surgeon known for his boundless energy didn’t slow down. He served as Cleveland Clinic’s president until 1940.

Dr. Crile “was the dynamo of the group, imaginative, creative, innovative and driving,” said his son George “Barney” Crile Jr., MD, a distinguished physician in his own right.

After Dr. George Crile Sr. died January 7, 1943, tributes poured in from around the world, but one from close to home summed him up best. Said Dr. Lower: “George Crile had a quest and a vision that he pursued throughout his entire adult life. He was not content to make use of known truths, but was forever searching for the answer to: What is life?”

William Lower, MD

1867-1948

In his later years, Dr. William Lower was known to walk around Cleveland Clinic, turning off lights to save electricity. Of the founders, he was the most business-minded, the one who checked every budget line. His thriftiness was just one side of the groundbreaking urologic surgeon, however.

Dr. Lower was born May 6, 1867. Like his cousin Dr. George Crile Sr., Dr. Lower grew up on a farm near Chili, Ohio. He graduated from Wooster University’s Medical Department in 1891. The following year, he joined Dr. Frank Bunts and Dr. Crile in a Cleveland practice.

From 1900 to 1901, Dr. Lower was a surgeon for the 9th U.S. Cavalry in the Philippines. During World War I, he served alongside Dr. Bunts and Dr. Crile in the Lakeside Unit in Rouen, France. There, the three physicians started discussing a hospital that would employ the practices of military medicine teamwork, a place where they could be their “own masters,” as Dr. Lower put it.

When Cleveland Clinic was under construction, the exacting Dr. Lower was known to check every brick. He applied the same stringent standards toward himself. As a surgeon, he was renowned for “keyhole-sized” incisions, so small that only he could successfully operate through them.

At Cleveland Clinic’s 25th anniversary in 1946, Dr. Lower extolled the founding principles of care, research and education, which remain integral to Cleveland Clinic’s mission to this day. The last surviving founder died June 17, 1948.

John Phillips, MD

1879-1929

Once described as “silent, confident and imperturbable,” Dr. John Phillips was the only founder who was not a surgeon. He was born February 18, 1879, in Welland, Ontario. After graduating from the University of Toronto medical school in 1903, he moved to the United States for an internship and residency at Lakeside Hospital in Cleveland, where he met Dr. George Crile Sr.

During World War I, Dr. Phillips was a captain in the U.S. Army Medical Corps. Like the other founders, he came to appreciate the military model of medical teamwork.

After the war, Dr. Phillips was approached by Dr. Frank Bunts, Dr. William Lower and Dr. Crile, who needed an internist for their new clinic. Dr. Phillips was not only a highly respected practitioner and teacher, but president-elect of the Academy of Medicine of Cleveland (which each of the other founders also had led as president). Tasked with building Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Internal Medicine, Dr. Phillips recruited many high-profile physicians.

He was in his office on the third floor of the Clinic Building on the morning of May 15, 1929, when X-ray film in the basement exploded. Dr. Phillips was able to leap to safety, but not before inhaling deadly fumes. Feeling tired, he went home to rest. In the afternoon, he called for Dr. Crile and Henry John, MD. “He knew what the score was,” Dr. John said. “We did not say a word.” Dr. Phillips died later that evening.

Watch "Innovation in Our DNA," a video about Cleveland Clinic's forward-thinking history. It's part of "A Century of Care," a series by Cleveland Clinic and the CNN content studio Courageous.